May 17 is recognized as World Telecommunication and Information Society Day to help raise awareness of the possibilities that the use of the Internet and other information and communication technologies can bring to societies and economies, as well as of ways to bridge the digital divide.

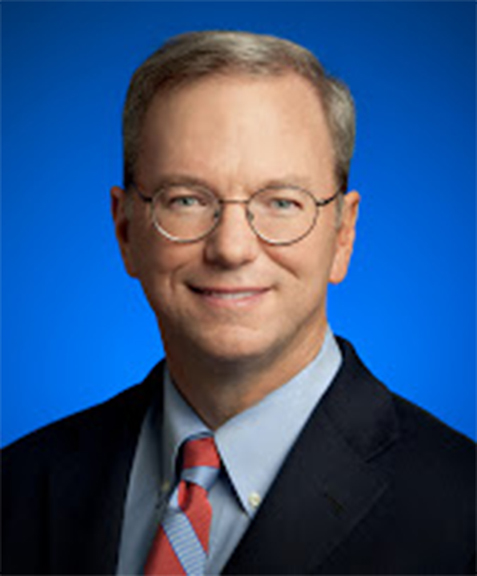

In 2011, at the Techonomy conference in California, Google Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt made a bold statement. “Every two days now we create as much information as we did from the dawn of civilization up until 2003. That’s something like five exabytes of data, he says. Let me repeat that,” he said. “We create as much information in two days now as we did from the dawn of man through 2003.”

In keeping with the nature of a “Techonomy,” Schmidt’s statement quickly went viral, with dozens of tech-pundits blogging and tweeting the astounding statistic. In quick succession, however, some of the more contrarian among them pointed out that either he was exaggerating, wrong or just full of, well, “malarkey.” Maybe Schmidt should have known better, that an information society would take his quote, turn it upside down, fact-check every little detail and use the World-Wide Web to tell anyone who would listen that he’d made a mistake. But, did he?

Schmidt, in my eyes, accomplished two things. First, amid all the digital clutter that travels the fiber-optic pipes, he was able to walk away from that conference with everyone talking about him, his company and what he said. That’s no small  feat. Second, if anyone was listening closely enough, they heard what he said next.

feat. Second, if anyone was listening closely enough, they heard what he said next.

“I spend most of my time assuming the world is not ready for the technology revolution that will be happening to them soon.”

The tsunami of information we’re seeing today is being generated by at least two complex, interrelated and powerful forces. The first is very popular in the press – Big Data, “a collection of data sets so large and complex that it becomes difficult to process,” at least according to Wikipedia, the online encyclopedia of more than 4.5 million English articles authored by more than 76,000 contributors. Indeed, in 2011 International Data Corporation published a report, Extracting Value from Chaos, which noted that, “The world’s information is doubling every two years. In 2011 the world will create a staggering 1.8 zettabytes. By 2020 the world will generate 50 times [that amount].”

Just last week, the White House released a report, Big Data: Seizing Opportunities, Preserving Values, which admitted concerns about the flood of data: “big data analytics have the potential to eclipse longstanding civil rights protections in how personal information is used in housing, credit, employment, health, education, and the marketplace.” Not to be too Orwellian, the report also assured the American public that Big Data “hold[s] within it solutions that can enhance accountability, privacy, and the rights of citizens. Properly implemented, big data will become an historic driver of progress, helping our nation perpetuate the civic and economic dynamism that has long been its hallmark.”

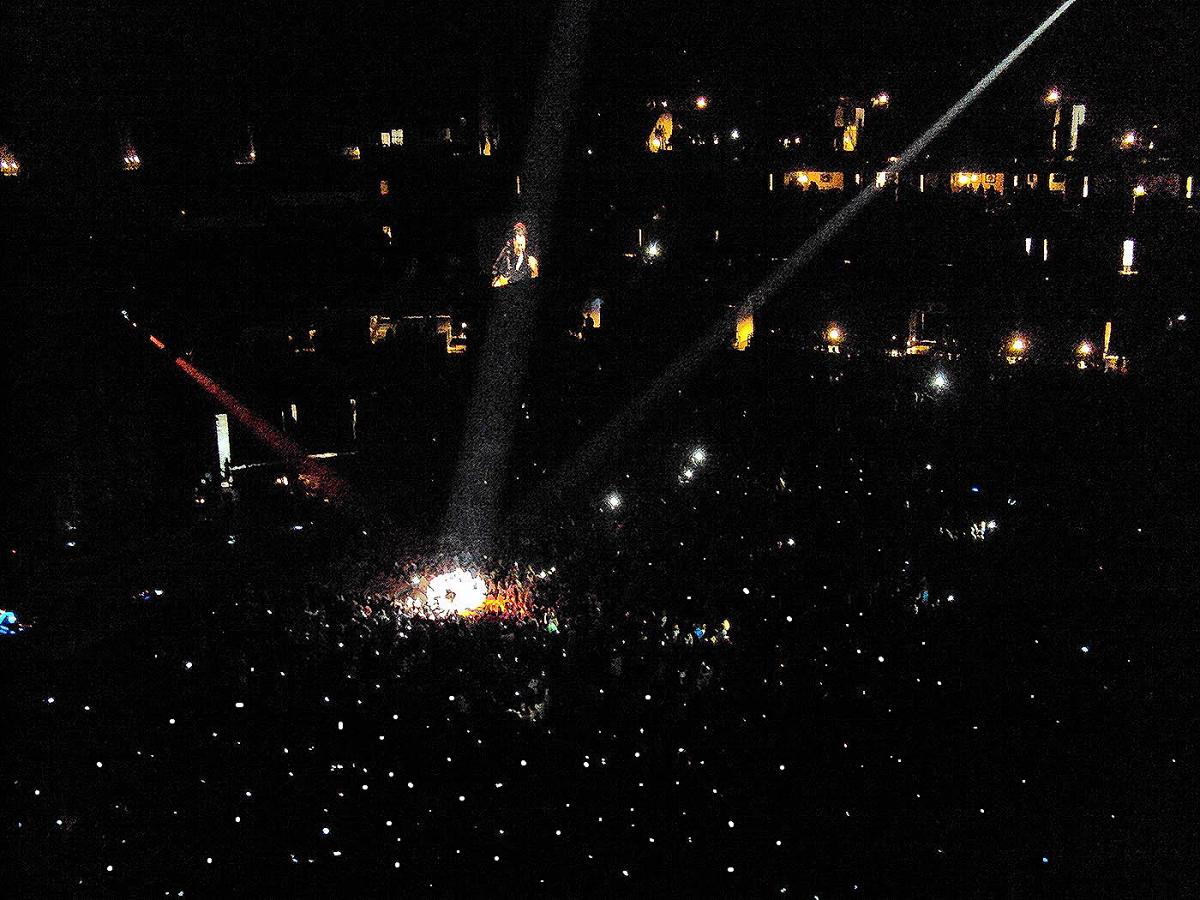

The other tidal force behind the data deluge is generated through the millions of personal, hand-held devices carried throughout each day by the billions of people around the planet. In a later study, IDC pointed out that “general consumers have accounted for around three-quarters” of the digital universe. IDC estimated that consumers generate more than 90  percent of the new data in the form of instant messages, digital images and motion videos. Just over a year ago, the International Telecommunications Union stated that the number of active cell phones would reach 7.3 billion sometime this year. Consider that for another moment … there will be more cell phones in use than there are humans on Earth.

percent of the new data in the form of instant messages, digital images and motion videos. Just over a year ago, the International Telecommunications Union stated that the number of active cell phones would reach 7.3 billion sometime this year. Consider that for another moment … there will be more cell phones in use than there are humans on Earth.

Undoubtedly, this glut of information is sometimes unwieldy and difficult to protect and raises legitimate privacy concerns. By now, about everyone is familiar with the controversy surrounding the tracking of phone data by the National Security Agency and the impact of customer data breaches at retailer Target. Yet, the information society still pleasantly surprises us week-in and week-out with the promise of a better world. In recent days, Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan was pressured by a worldwide social media tempest to commit to undertaking rescue efforts for more than 200 schoolgirls abducted by an Islamist militant group. A groundswell of digital indignation over racist remarks by basketball team owner Donald Sterling forced the NBA to act swiftly and decisively in banning him for life and to attempt to force him to sell his team.

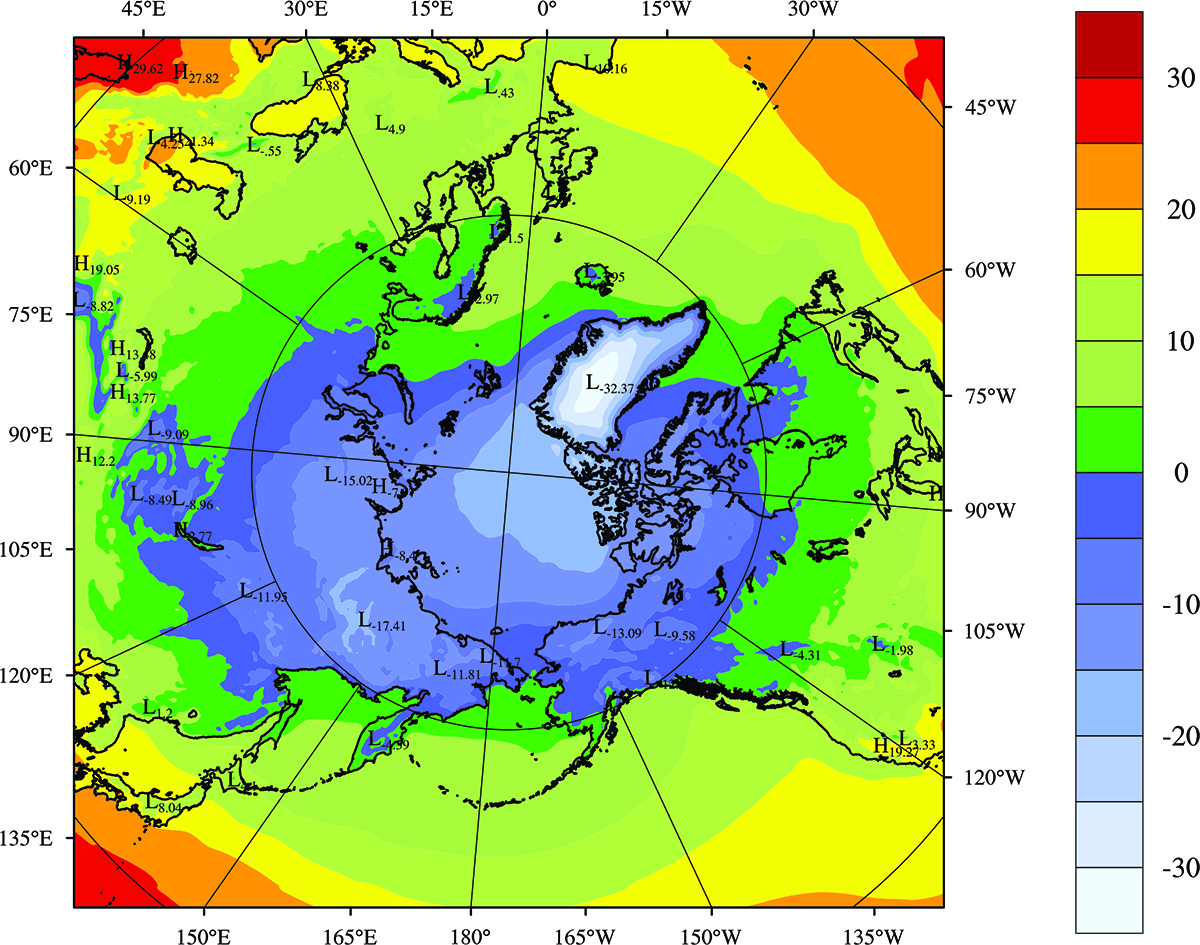

At the same time, scientists, such as those leveraging the resources of the Ohio Technology Consortium, are continually finding brilliant ways to turn this deluge of data into innovations and discoveries. For example, using the computational  might of the Ohio Supercomputer Center, Ohio State’s Dr. David Bromwich is synergizing terabytes of polar weather data from more than 11 years to create benchmarks that will lead to more accurate climate projections. Paul Schopis at OARnet is working with a research team to perfect a “Science DMZ,” a high-speed, sub-network on the Internet that allows researchers to safely share large volumes of data unencumbered by the firewalls that typically safeguard, but constrain, data between university campuses. Lastly, OhioLINK is examining the digital preservation challenges posed by large data sets, beginning with their own Electronic Theses and Dissertations Center, a collection of more than 40,000 theses and dissertations from Ohio students, and the Electronic Journal Center, with more than 22 million academic journal articles.

might of the Ohio Supercomputer Center, Ohio State’s Dr. David Bromwich is synergizing terabytes of polar weather data from more than 11 years to create benchmarks that will lead to more accurate climate projections. Paul Schopis at OARnet is working with a research team to perfect a “Science DMZ,” a high-speed, sub-network on the Internet that allows researchers to safely share large volumes of data unencumbered by the firewalls that typically safeguard, but constrain, data between university campuses. Lastly, OhioLINK is examining the digital preservation challenges posed by large data sets, beginning with their own Electronic Theses and Dissertations Center, a collection of more than 40,000 theses and dissertations from Ohio students, and the Electronic Journal Center, with more than 22 million academic journal articles.

In the end, information is flooding the planet, and the people of the world will choose to use it for good or bad. As with other universally impactful innovations – firearms, the printing press, automobiles, television and radio and, now, information – the great majority of people will learn how to leverage information for the betterment of their families, their communities and the Earth. Eric Schmidt wasn’t wrong when he said, “the world is not ready for the technology revolution that will be happening to them,” because the world has never been ready for changes. But they adapt.